The World of Islam

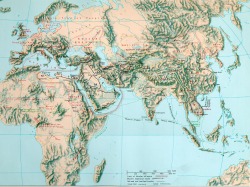

The Spread of Islam

From the oasis cities of Makkah and Madinah in the Arabian Desert, the message of Islam went forth with electrifying speed. Within half a century of the Prophet's death 632 AD, Islam had spread to three continents. Islam is not, as some imagine in the West, a religion of the sword nor did it spread primarily by means of war. It was only within Arabia, where a crude form of idolatry was rampant, that Islam was propagated by warring against those tribes which did not accept the message of God--whereas Christians and Jews were not forced to convert. Outside of Arabia also the vast lands conquered by the Arab armies in a short period became Muslim not by force of the sword but by the appeal of the new religion. It was faith in One God and emphasis upon His Mercy that brought vast numbers of people into the fold of Islam. The new religion did not coerce people to convert. Many continued to remain Jews and Christians and to this day important communities of the followers of these faiths are found in Muslim lands.

Moreover, the spread of Islam was not limited to its miraculous early expansion outside of Arabia. During later centuries the Turks embraced Islam peacefully as did a large number of the people of the Indian subcontinent and the Malay-speaking world. In Africa also, Islam has spread during the past two centuries even under the mighty power of European colonial rulers. Today Islam continues to grow not only in Africa but also in Europe and America where Muslims now comprise a notable minority.

General Characteristics of Islam

Islam was destined to become a world religion and to create a civilization which stretched from one end of the globe to the other. Already during the early Muslim caliphates, first the Arabs, then the Persians and later the Turks set about to create classical Islamic civilization. Later, in the 13th century, both Africa and India became great centers of Islamic civilization and soon thereafter Muslim kingdoms were established in the Malay-Indonesian world while Chinese Muslims flourished throughout China.

Global Religion

Islam is a religion for all people from whatever race or background they might be. That is why Islamic civilization is based on a unity which stands completely against any racial or ethnic discrimination. Such major racial and ethnic groups as the Arabs, Persians, Turks, Africans, Indians, Chinese and Malays in addition to numerous smaller units embraced Islam and contributed to the building of Islamic civilization. Moreover, Islam was not opposed to learning from the earlier civilizations and incorporating their science, learning, and culture into its own world view, as long as they did not oppose the principles of Islam. Each ethnic and racial group which embraced Islam made its contribution to the one Islamic civilization to which everyone belonged. The sense of brotherhood and sisterhood was so much emphasized that it overcame all local attachments to a particular tribe, race, or language--all of which became subservient to the universal brotherhood and sisterhood of Islam.

The global civilization thus created by Islam permitted people of diverse ethnic backgrounds to work together in cultivating various arts and sciences. Although the civilization was profoundly Islamic, even non-Muslim "people of the book" participated in the intellectual activity whose fruits belonged to everyone. The scientific climate was reminiscent of the present situation in America where scientists and men and women of learning from all over the world are active in the advancement of knowledge which belongs to everyone.

The global civilization created by Islam also succeeded in activating the mind and thought of the people who entered its fold. As a result of Islam, the nomadic Arabs became torch-bearers of science and learning. The Persians who had created a great civilization before the rise of Islam nevertheless produced much more science and learning in the Islamic period than before. The same can be said of the Turks and other peoples who embraced Islam. The religion of Islam was itself responsible not only for the creation of a world civilization in which people of many different ethnic backgrounds participated, but it played a central role in developing intellectual and cultural life on a scale not seen before. For some eight hundred years Arabic remained the major intellectual and scientific language of the world. During the centuries following the rise of Islam, Muslim dynasties ruling in various parts of the Islamic world bore witness to the flowering of Islamic culture and thought. In fact this tradition of intellectual activity was eclipsed only at the beginning of modern times as a result of the weakening of faith among Muslims combined with external domination. And today this activity has begun anew in many parts of the Islamic world now that the Muslims have regained their political independence.

A Brief History of Islam

The Rightly guided Caliphs

Upon the death of the Prophet, Abu Bakr, the friend of the Prophet and the first adult male to embrace Islam, became caliph. Abu Bakr ruled for two years to be succeeded by 'Umar who was caliph for a decade and during whose rule Islam spread extensively east and west conquering the Persian empire, Syria and Egypt. It was 'Umar who marched on foot at the head of the Muslim army into Jerusalem and ordered the protection of Christian sites. 'Umar also established the first public treasury and a sophisticated financial administration. He established many of the basic practices of Islamic government.

'Umar was succeeded by 'Othman who ruled for some twelve years during which time the Islamic expansion continued. He is also known as the caliph who had the definitive text of the Noble Quran copied and sent to the four corners of the Islamic world. He was in turn succeeded by 'Ali who is known to this day for his eloquent sermons and letters, and also for his bravery. With his death the rule of the "rightly guided" caliphs, who hold a special place of respect in the hearts of Muslims, came to an end.

The Caliphate

Umayyad

The Umayyad caliphate established in 661 was to last for about a century. During this time Damascus became the capital of an Islamic world which stretched from the western borders of China to southern France. Not only did the Islamic conquests continue during this period through North Africa to Spain and France in the West and to Sind, Central Asia and Transoxiana in the East, but the basic social and legal institutions of the newly founded Islamic world were established.

established.

Abbasids (750 CE- 1258)

The Abbasids, who succeeded the Umayyads, shifted the capital to Baghdad which soon developed into an incomparable center of learning and culture as well as the administrative and political heart of a vast world.

They ruled for over 500 years but gradually their power waned and they remained only symbolic rulers bestowing legitimacy upon various sultans and princes who wielded actual military power. The Abbasid caliphate was finally abolished when Hulagu, the Mongol ruler, captured Baghdad in 1258, destroying much of the city including its incomparable libraries.

While the Abbasids ruled in Baghdad, a number of powerful dynasties such as the Fatimid’s, Ayyubids and Mamluks held power in Egypt, Syria and Palestine. The most important event in this area as far as the relation between Islam and the Western world was concerned was the series of Crusades declared by the Pope and espoused by various European kings. The purpose, although political, was outwardly to recapture the Holy Land and especially Jerusalem for Christianity. Although there was at the beginning some success and local European rule was set up in parts of Syria and Palestine, Muslims finally prevailed and in 1187 Saladin, the great Muslim leader, recaptured Jerusalem and defeated the Crusaders.

North Africa and Spain

When the Abbasids captured Damascus, one of the Umayyad princes escaped and made the long journey from there to Spain to found Umayyad rule there, thus beginning the golden age of Islam in Spain. Cordoba was established as the capital and soon became Europe's greatest city not only in population but from the point of view of its cultural and intellectual life. The Umayyads ruled over two centuries until they weakened and were replaced by local rulers.

Meanwhile in North Africa, various local dynasties held sway until two powerful Berber dynasties succeeded in uniting much of North Africa and also Spain in the 12th and 13th centuries. After them this area was ruled once again by local dynasties such as the Sharifids of Morocco who still rule in that country. As for Spain itself, Muslim power continued to wane until the last Muslim dynasty was defeated in Granada in 1492 thus bringing nearly eight hundred years of Muslim rule in Spain to an end.

After the Mongol Invasion

The Mongols devastated the eastern lands of Islam and ruled from the Sinai Desert to India for a century. But they soon converted to Islam and became known as the Il-Khanids. They were in turn succeeded by Timur and his descendents who made Samarqand their capital and ruled from 1369 to 1500. The sudden rise of Timur delayed the formation and expansion of the Ottoman empire but soon the Ottomans became the dominant power in the Islamic world.

Ottoman Empire

From humble origins the Turks rose to dominate over the whole of Anatolia and even parts of Europe. In 1453 Mehmet the Conqueror captured Constantinople and put an end to the Byzantine empire. The Ottomans conquered much of Eastern Europe and nearly the whole of the Arab world, only Morocco and Mauritania in the West and Yemen, Hadramaut and parts of the Arabian Peninsula remaining beyond their control. They reached their zenith of power with Suleyman the Magnificent whose armies reached Hungary and Austria. From the 17th century onward with the rise of Western European powers and later Russia, the power of the Ottomans began to wane. But they nevertheless remained a force to be reckoned with until the First World War when they were defeated by the Western nations. Soon thereafter Kamal Ataturk gained power in Turkey and abolished the six centuries of rule of the Ottomans in 1924.

Persia

While the Ottomans were concerned mostly with the western front of their empire, to the east in Persia a new dynasty called the Safavids came to power in 1502. The Safavids established a powerful state of their own which flourished for over two centuries and became known for the flowering of the arts. Their capital, Isfahan, became one of the most beautiful cities with its blue tiled mosques and exquisite houses. The Afghan invasion of 1736 put an end to Safavid rule and prepared the independence of Afghanistan which occurred formally in the 19th century. Persia itself fell into turmoil until Nader Shah, the last Oriental conqueror, reunited the country and even conquered India. But the rule of the dynasty established by him was short-lived. The Zand dynasty soon took over to be overthrown by the Qajars in 1779 who made Tehran their capital and ruled until 1921 when they were in turn replaced by the Pahlavis.

India

As for India, Islam entered into the land east of the Indus River peacefully. Gradually Muslims gained political power beginning in the early 13th century. But this period which marked the expansion of both Islam and Islamic culture came to an end with the conquest of much of India in 1526 by Babur, one of the Timurid princes. He established the powerful Mogul empire which produced such famous rulers as Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan and which lasted, despite the gradual rise of British power in India, until 1857 when it was officially abolished.

Malaysia and Indonesia

Farther east in the Malay world, Islam began to spread in the 12th century in northern Sumatra and soon Muslim kingdoms were established in Java, Sumatra and mainland Malaysia. Despite the colonization of the Malay world, Islam spread in that area covering present day Indonesia, Malaysia, the southern Philippines and southern Thailand, and is still continuing in islands farther east (http://www.barkati.net/english/)

Islam in Africa

Summary Islam is a crucial cultural, religious and political force throughout Africa, counting more than one-third of the continent’s inhabitants among the faithful. This article traces the history of Islam since the early seventh century to its current status and emergence as an alternative system for organizing the social, political and economic life of Muslims.

Today, Islam in Africa has rooted itself with a distinct local flavour. The spiritual masters, with their deep-rooted visions and strong educational programmes, have been recognized as having played a key role in interpreting Islam for the specific needs of African Muslims.

Islam is a crucial cultural, religious and political force throughout Africa, yet when one thinks of Africa, the idea that more than a third (307 million) of the continent’s estimated 770 million inhabitants are of Muslim faith may not cross the mind immediately. (See the table: "Statistics on Islam in selected African nations" at the end of this article). This is partly because of the erroneous notion that many African countries -- notably those in the northern parts -- are considered either part of the Arab world or a subsection of the Middle East.

Countries like Senegal, Mali and Somaliland are mostly Muslim. Half of Nigeria’s 113 million inhabitants -- Africa’s most populous nation -- are proponents of the Islamic faith. In addition, Africa’s remaining two most populous nations, Egypt and Ethiopia, have a Muslim population of 94 % and 59.68 % respectively. Furthermore, there are large Muslim communities in Ghana, Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania.

In short, Islam is very much an African religion with African roots and, as such, has been an important part of the political and cultural development and evolution of many African nations. Muslims were crucial in creating commercial networks with the rest of the world, in state building, in introducing literacy (when Muslims were in charge of state records), as well as in exchanges of inter-state diplomacy within Africa and beyond.

History When did Islam take root in Africa? The historian Basil Davidson provides some answers in his text Africa in History:

Of the headlong rush of Islam through North Africa and Spain, the dates speak almost for themselves. They are dramatic dates; even, at first sight, impossibly so. On 16 July 622, four men traveling on two camels left Mecca (the initial heartland of Islam) for another obscure Arabian town, Medina. Within as few as twenty-two years the movement of religious and political revolution thus set going by Muhammad (the Prophet of Islam) had won the whole of Arabia and Syria, engulfed Egypt, seized the Byzantine fortress at the southern apex of the delta of the Nile, captured Alexandria, and was everywhere preparing new departures.

Prior to the date 622 provided above, Muslims fondly recall that the king of Abyssinia, Negus, provided shelter to Muslims escaping persecution from the Meccans in 615. Later King Negus accepted Islam.

Another historical question remains: How do we hope to explain how the Muslim faith of the Arab conquerors, who entered Africa from Tunisia (670, Uqba ibn Nafi), Morocco (683), Ghana (900), Mali (1000), and later East Africa by trading missions, could take root and flourish among peoples who owed nothing to the Arabs, knew little of them and did not speak the Arabic language?

The answer seems to lie with the fact that Arab conquerors could not simply appear as conquerors, but “also as renovators, as leaders who could point the way to a better order of society”. A society that -- in the words of Basil Davidson -- “bore the light of tolerance and social progress through centuries when Europe, impoverished, provincialised and almost illiterate, lay in distant battle and confusion”.

Europe and the barbarian raiders of the north, led by the Vandals, Goths, Franks and Visigoths two centuries earlier, failed to impress the Berber tribes of Africa. The culture of embracing many people remained beyond their grasp. It was largely due to these limitations and the social insecurity and turmoil long experienced that the Muslim case triumphed where its contesters failed.

Political Change The greatest socio-political and cultural impact of Islam in the last few decades has understandably been in the Arabised part of the continent, such as Egypt, Sudan and north Africa, which came under Arab-Muslim cultural and political influence during the seventh to eighth centuries -- early in the history of Islam.

However, other African countries with Muslim majorities or substantial minorities have also been affected by the influences emanating from Islam. Former South African president Nelson Mandela has regularly made reference to the key role South African Muslims played in the liberation of South Africa from apartheid. In this respect, this vocal Muslim minority community assumes a more assertive cultural identity and engages in civic and political activity.

An important feature of Islam in the last three decades has been its political reshaping. Therefore, it has emerged as an alternative system for organizing the social, political and economic life of Muslims.

Islamic Movement This has given rise to the Islamic movement phenomenon in its various shapes. The methods applied by various groups and movements to bring about an Islamic system have differed from country to country and from time to time, ranging from mild efforts to assist the cultural Islamisation of society, to efforts to gain power through electoral means, to acts of violence.

The most dramatic example of how the Islamic movement’s efforts to implement their vision can lead to conflict and bloodshed has been the Algerian civil war, which began in 1992 when Algeria’s Islamic groups were denied the fruit of their electoral victory. The war has subsided somewhat, but it has not completely ended. Nor has Algeria succeeded in healing its wounds and developing a new national consensus.

Meanwhile, Algeria’s example has been used as a pretext by some governments to avoid political liberalisation, disallowing a voice even to moderate Muslims who would like to advance their views within a democratic framework.

However, the dilemma is real, and as long as all major Muslim groups have not accepted the clarion principles of democracy, it will remain so. During 2000, two major African countries--Nigeria and Morocco--embarked on a process of liberalisation. In Nigeria’s case, this meant a return to the democratic process after years of military rule. In the case of Morocco, it meant a move towards political liberalisation. In Nigeria, the return to democracy reopened some of the old issues that have long divided the mostly Muslim north and the mostly Christian south.

The most contentious has been the north’s demand for the implementation of the Shari'ah, forms of Islamic penal law that govern the nature of punishments for criminals, as well as social behaviour.

Nigeria In studying the evolution of political Islam in Nigeria, scholars have provided the historical background to the evolution of Nigerian Islam and show how issues of ethnicity, religion, class and economic interests have interacted to create the present circumstances of conflict. Many analysts have shown how the precepts of Islam, such as Shari’ah, have been appropriated in the struggle for the resources of Nigeria.

The conclusion scholars have reached is that “as long as Nigeria’s social and economic problems persist, the risk of manipulation of religion for political purposes and/or the practice of resorting to religion to find answers to problems of the material world will remain”. However, the restoration of democracy to Nigeria provides some hope that the current problems and tensions will not reach a point where widespread conflict becomes likely.

However, for the democratic process to have a chance to succeed, some rapid improvement in Nigeria’s economic conditions -- especially a reduction in the level of unemployment -- is necessary.

Morocco In Morocco, by contrast, political liberalisation initiated by King Muhammad VI has opened new possibilities for the Islamic forces to play a constructive role in their country’s politics, such as the Al-Islah wa at-Tawhid (Reform and Unity c -1982) and Al-`Adl wal Ihsaan (Justice and Goodness c - 1985). The question now posed by observers is whether they will use this opportunity wisely.

At present, it appears unlikely that Morocco will face a state-threatening challenge from Islamic groups. In the meantime, commentator Mecham notes, “finding an effective mechanism for incorporating Islamist groups into the political process without threatening the consolidation of liberal political reform remains a principal challenge for the new king and Morocco’s political leaders, secular and Islamist alike”.

Meanwhile, relations between states and Islamic movements in other North African countries, such as Tunisia and Egypt, remain tense.

Islam Today Today, Islam in Africa has rooted itself with a distinct local flavor. The spiritual masters, with their deep-rooted visions and strong educational programs, have been recognized as having played a key role in interpreting Islam for the specific needs of Africans. From the early 1970s vigorous external attempts have been made to “re-root” Islam on the continent. Such theological attempts, while sincere, have added and at times disturbed the fine religious ecology of Africa.

(http://www.nuradeen.com/CurrentIssues/IslamInAfrica.htm).

Islam in South Africa

The Cape of Good Hope was a refreshment station for the Dutch East India Company (DEIC) and a place to send exiled and dethroned rulers from its eastern provinces. Many of these political exiles were some of the first Muslims in South Africa, an example being Sheikh Yusuf of Mucassar (Indonesia), who arrived in the second half of the 17th century with his family and entourage totaling 49 people. His dwellings on the False Bay Coast attracted fugitive slaves and other easterners, and are the first evidence of the establishment of Islam and its dissemination among slaves on the Cape. Consequently, Sheikh Yusuf is considered the founder of Islam on the Cape of Good Hope.

According to historians, the earliest Cape Muslim leaders were freed convicts from Dutch colonies such as Malaysia and the Indonesian archipelago, but their crimes are not stated. I wonder if it was their resistance, or their mere Islamic faith that enraged their Dutch colonizers. These “freed convict” imams arrived at the Cape in several migrations throughout the 18th century and made up most of the ‘ulamaa’ there.

Slave raiding in West Africa was prohibited in the 18th century to the DEIC, so they turned to the Indian Sub-continent, which supplied more than half of the formal slaves. The Indonesian archipelago supplied just less than a quarter, a little more than half came from Madagascar, the Mascarene Islands of the Indian Ocean, and the East African coast. The mosques and Jumu`ah Prayers of these groups were first noticed in 1770 by the English explorer George Forster.

The Dutch Reformed Church prohibited slaves from converting to Christianity because they could not then be sold, so the slaves turned to Islam. Achmat Davids noted that Muslim slave owners were also slow in manumitting Muslim slaves at their death. Despite that, the several hundred male slaves who bought their freedom, or whose owners willingly freed them, still converted to Islam. The Muslim free blacks not only freed their own slaves, but also manumitted others, whatever their religion. The Christian missionary John Philip in 1831 wrote admirably about this incident.

I do not know whether there is a law among the Malays bidding them to make their slaves free, but it is known that they seldom retain in slavery those that embrace their religion. And to the honor of the Malays, it must be stated that many instances have occurred in which, at public sales, they have purchased aged and wretched creatures, irrespective of their religion, to make them free.

It was rare to find Christian slave owners displaying such egalitarianism with their Christian slaves.

The Merdeka Muslim slaves were those set free to take part in the wars against the British and then the Xhosa. African slaves that the British navy intercepted at sea were liberated and diverted to Cape Town, where they converted to Islam in large numbers. Muslims on the Cape traded with other Muslims such as Makkan ‘ulamaa’ who, having arrived at the Cape, sometimes married and settled there. The 1830s are the earliest record of Hajjis going to Saudi Arabia via Mauritius. The Cape ‘ulamaa’ were the first Cape Muslims to go to Hajj and write religious and other books in the new Arabic-Afrikaans. They established Islamic schools, manumitted slaves, ran mosques, conducted marriages and funerals, and generally successfully corresponded with the colonial authorities. The Cape Muslims complained to Queen Victoria about having no Muslim “missionary,” so she sent the Kurdish scholar Sheikh Abu Bakr Effendi to them in 1862.

The second wave of immigration was the indentured Indians, who made up 80–90 percent of the second shipments to Natal. They were brought over to work in the sugarcane fields and mines of the newly colonized province of Natal on the east coast. These indentured Indians were supplemented with others from the Zanzibar and Pemba islands.

Correspondence between Al-Hajj Mustafa Al-Transvaali and the Grand Mufti of Egypt Muhammad ‘Abduh, on questions concerning Muslims living as a minority in a non-Muslim land, indicated the development of Muslim early 20th century thought in South Africa.

The Muslims succeeded in founding the Jami`at Al-`Ulamaa’ in Transvaal in 1923, the Muslim Judicial Council in Cape Town in 1945, and the Jami`at Al-`Ulamaa’ in Natal in 1952. However, it seems that they were based upon ethnic and geographical lines that were to be the basis, perhaps, for differentiating between them in the apartheid system (1948–1994).

In 1990, delegates from Muslim organizations gathered to consider their response to a post-apartheid South Africa. The outcome was the formation of the Muslim Front that campaigned for the ANC in 1994. Some Muslims formed alternative parties, but these failed to win seats in the new Assembly. However, the ANC appointed `Abdullah Omar to the portfolio of justice in the government of national unity.

Due to the failure of government to create lasting law and order in recent times, there has been a revival of Islamic education for the youth, and the emergence of Muslim grassroots community organizations such as PAGAD (People Against Gangsterism and Drugs) in Capetown(http://www.islamonline.net/english/In_Depth/MuslimAfrica/articles/2005/04/article01.shtml).